In 2022, we participated in Orange County’s first-ever Creek Week. Celebrating our creeks with Orange County, Town of Chapel Hill, Town of Carrboro, Town of Hillsborough, and OWASA has been a highlight of our spring semester. As a University, there’s a constant flow of exciting research coming from scientists, courses, and field sites. At Sustainable Carolina, we celebrate our creeks throughout the year and and look to improve watershed health via research, service, and engagement activities.

In 2022, we participated in Orange County’s first-ever Creek Week. Celebrating our creeks with Orange County, Town of Chapel Hill, Town of Carrboro, Town of Hillsborough, and OWASA has been a highlight of our spring semester. As a University, there’s a constant flow of exciting research coming from scientists, courses, and field sites. At Sustainable Carolina, we celebrate our creeks throughout the year and and look to improve watershed health via research, service, and engagement activities.

Trash bags and pickers in hands, UNC Environment, Health and Safety and UNC Institute for the Environment staff waded into the woods – and creeks – in search of litter. In total, staff spent two hours at the Dean Smith outfall picking up trash found underneath leaves, embedded in the dirt, and twisted in tree roots along the creek bank.

Picking up the trash around creeks is a form of defense for our waterways, preventing it from making its way further downstream. When you’re living in a watershed that flows into a reservoir where people get their drinking water, this is especially important.

Janet Clarke, a stormwater specialist with UNC Environment, Health and Safety, said the Dean Smith outfall tends to collect a lot of trash from the storm drain system and adjacent roadways.

“Most of UNC’s campus drains to Meeting of the Waters Creek,” Clarke said. “Over time, the creek and creek bank collect trash that has been discarded either accidentally or intentionally around campus. This trash Is harmful to wildlife for many reasons; it can be mistaken for food, it adds microplastics and chemical contaminants into the water when the materials break down, and it can physically trap wildlife.”

The outfall, located on UNC-Chapel Hill’s South Campus, is just one small part of the University’s stormwater system, which consists of thousands of catch basins and inlets, more than 60 miles of piping, and hundreds of stormwater control measures and outfalls. These modifications on campus help slow down water and improve its quality.

“The University has been developed for hundreds of years,” UNC-Chapel Hill Chief Sustainability Officer Dr. Mike Piehler said. “When you change a natural landscape, it changes the way things are transported.”

Unfortunately for our waterways, increased development leads to a variety of challenges. At Sustainable Carolina, we’re connected with researchers studying water through a sustainability lens year-round, not just here on campus, but throughout the state.

Nutrients Moving Through our Creeks

Nutrients Moving Through our Creeks

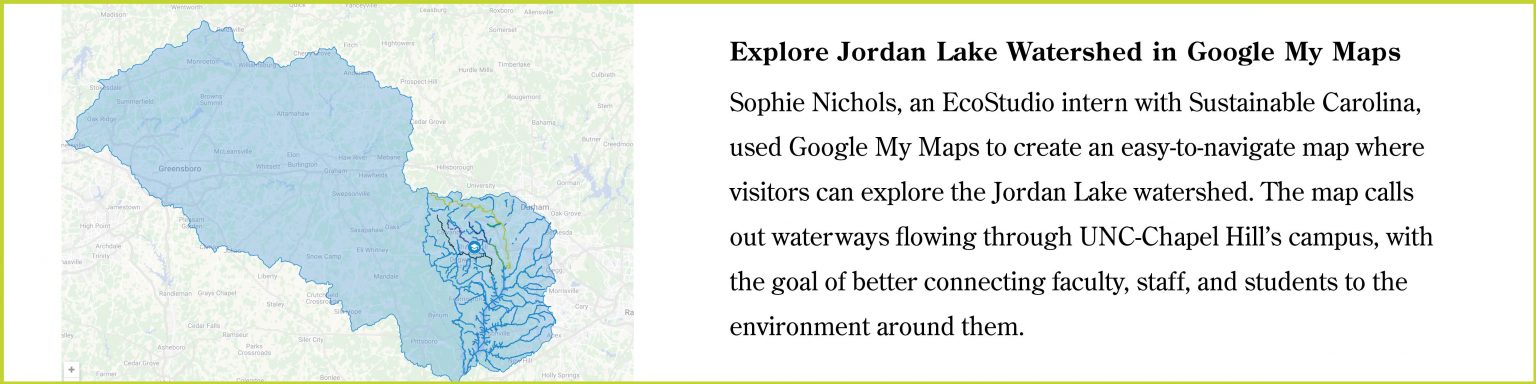

Campus lies within the Jordan Lake watershed, meaning that any falling water makes its way through the University’s catch basins, creeks, piping, and outfalls until it ultimately reaches Jordan Lake. As a man-made reservoir and drinking water source for more than half a million people living in the Triangle, its history of pollution is a concern, especially as we begin to experience more extreme rain events.

In 2009, the North Carolina General Assembly passed the Jordan Lake Rules, aimed at reducing the amount of nitrogen and phosphorus making its way to the water body and causing uncontrollable algal growth. Seven years later, the General Assembly asked the North Carolina Policy Collaboratory at UNC Chapel Hill to conduct a multi-year study on nutrient management strategies and water quality of Jordan Lake and Falls Lake.

“Reservoirs are different from lakes – they occur in places where there hasn’t been water forever,” Dr. Piehler noted. “When water hasn’t been retained in places with a lot of sun and then begins to be retained, this change can lead to increased algal growth.”

Dr. Piehler, who worked on the study, said the team analyzed the Jordan Lake Rules to see if they made sense and were appropriate. They also quantified limiting nutrients, or nutrients that impact the health of a waterbody and the organisms living there.

The study also considered the finances involved in managing the reservoir, how to pay, and who should pay. The paying aspect is a challenge because not everyone living within the Jordan Lake watershed drinks the water. Despite being located within the watershed, Chapel Hill receives its drinking water from Cane Creek Reservoir and University Lake.

Through this collaboration with researchers from universities across the central part of the state came several key takeaways. They found wastewater treatment plants within the watershed contributed a substantial amount of nitrogen and phosphorus to Jordan Lake. In addition to this, undeveloped lands contributed less nitrogen and phosphorus than surrounding developed areas – indicating that as the area continues to develop, nutrient loading will increase.

Dr. Piehler now leads the Sustainable Triangle Field Site, and this semester, students developed a project within the Jordan Lake watershed. More specifically, they’re placing pressure sensors in creeks at several locations across campus to study flooding and community resilience.

“We’re on top of a hill and all of the water flows down that hill,” Dr. Piehler said. “Our Sustainable Triangle Field Site looks at the university through a broad sustainability lens, looking at how our water use and development affects the water cycle.”

Microplastics at Highlands Biological Field Site

Microplastics at Highlands Biological Field Site

More than 300 miles away and in an entirely different watershed – the Cullasaja River watershed – Jason Love, associate director of Highlands Biological Station, Western Carolina University, studies another type of pollution threatening our waterways.

Larger than nutrients, some microplastics can be seen without the aid of a microscope. Ranging in size from 5 mm to .0001 mm in length, microplastics include things like microbeads, car tires, and clothing fibers. Microplastics can also result from the mechanical breakdown of bigger parent plastics.

“I was hearing more and more about microplastics in the literature, and nothing had been done in North America or freshwater rivers in the southeast,” Love said. “I thought, ‘let’s see if we can find an organism that would be a suitable bioindicator and useful metric for indicating the health of a waterway.’”

In 2018, Love began his first microplastics study at University of Georgia’s Coweeta Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) program. With the help of two high school students, he collected Asian clams, a species invasive to the United States, from Little Tennessee and Tuckasegee Rivers. After dissolving the flesh of the clams, they counted the number of microplastics left behind.

Following that initial study and a move to the Highlands Biological Station at Western Carolina University, Love became eager to look at the Chattooga River, which receives a lot of attention as part of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. After receiving permission from U.S. Forest Service and a private landowner, UNC-CH Highlands Field Site students began sampling water using ISCO automated water samplers.

“The great thing about being at a field station is that if we can collect a couple months of data and then do it again in five years, we’ll be able to see trends within the streams,” Love said.

Love plans to repeat the study with future HFS cohorts. He hopes to use samplers that funnel water into a container to see what plastics might be coming from surrounding roadways.

Though microplastics are already floating through our waterways there are things we can do to mitigate future harm and make our water systems more sustainable. Love said that at an individual level, we can do our part by consuming more consciously, reducing our plastic consumption, and participating in cleanups.