Priding itself on sustainability, BeAM introduced a new sustainable 3D printing filament, allPHA, to two of its makerspaces this spring. Sustainable Carolina partnered with BeAM and provided funding to quickly introduce the biodegradable filament into the space.

In 2014, Carolina opened its first makerspace – 400 square feet in Kenan Science Library. Today, campus is home to several makerspaces. Three of these are part of the BeAM@CAROLINA, which is open to all students, staff, and faculty at Carolina.

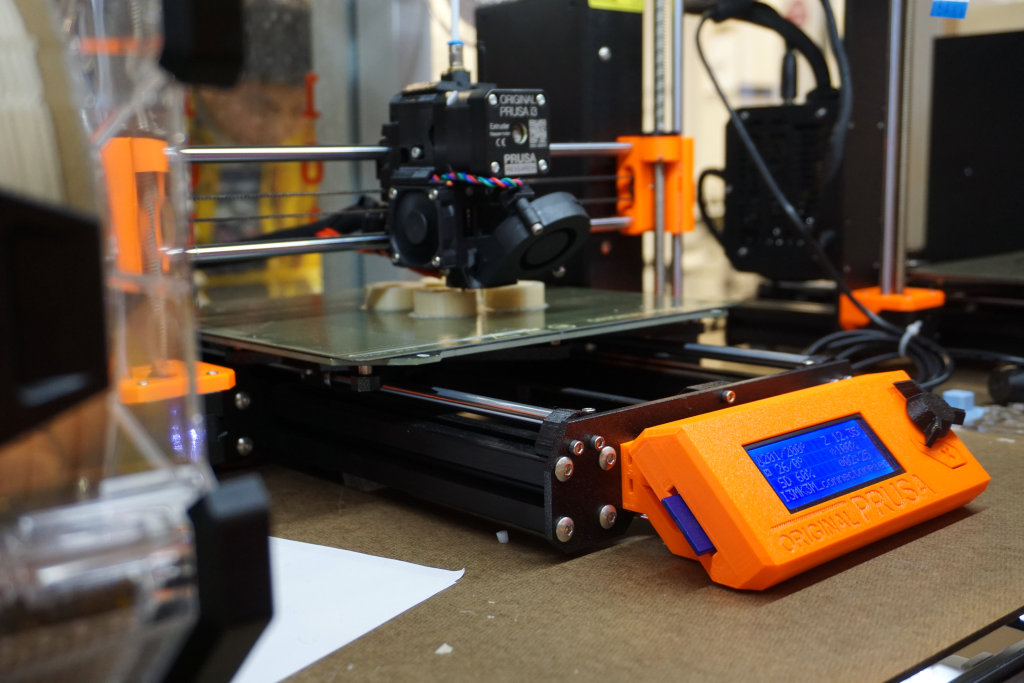

In two of these spaces, students can design an object on their computers then bring it to life through 3D printing. During printing, threadlike material called filament is fed into the printers, then laid down in layers on a plate below. Once all the layers are down, the 3D object is complete. However, not all projects are successes, and because most filament is plastic, failed 3D printed projects end up in the .

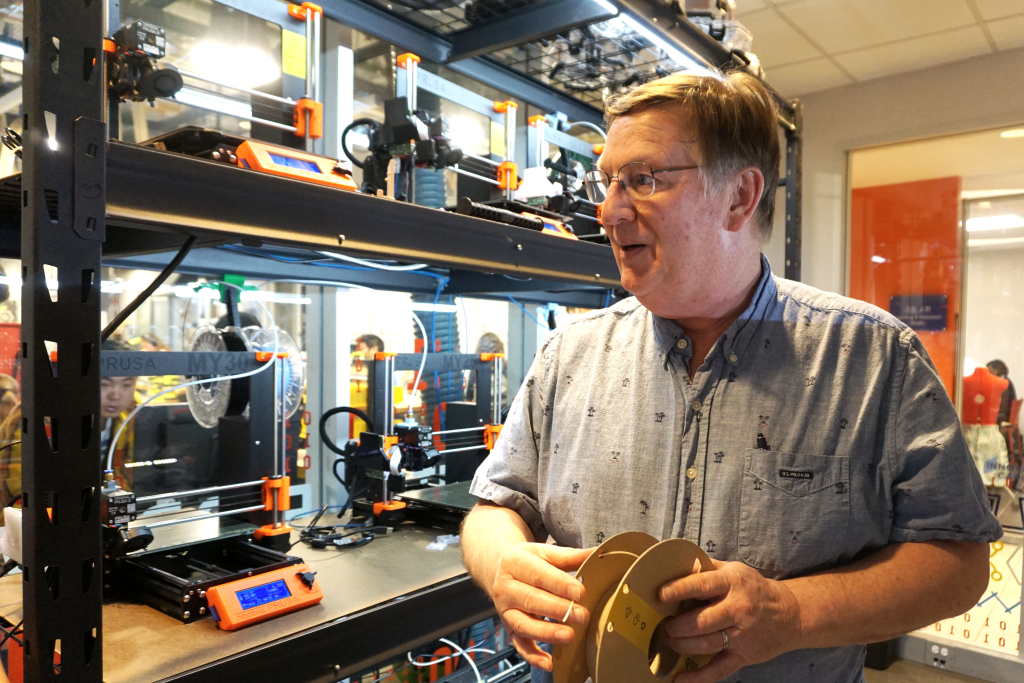

“The vast majority of 3D printing is waste,” said Glenn Walters, BeAM’s senior technical advisor. “But with colorFabb’s allPHA, you don’t even need a recycling stream – it’s compostable.”

Eastman Chemical Company has generously supplied BeAM with colorFabb’s XT (a co-polymer polyester, or CPE) filament for years. In 2022, colorFabb’s new, biodegradable allPHA (pronounced alpha) filament became available. At that point, BeAM started thinking about ways to supplement the strong, temperature-resistant XT filament with this new, sustainable filament.

By offering allPHA in its spaces, BeAM is decreasing its waste footprint. BeAM is also researching ways to reprocess and reuse this material.

3D Printing With allPHA

In the Murray makerspace, Walters points to the PRUSA 3D printers where students can make objects out of allPHA filament. PRUSA printers in Carmichael will be set up with the new filament soon. In both spaces, some UltiMaker printers can print with allPHA as well.

According to colorFabb, using allPHA reduces both greenhouse gases and environmental plastics pollution, while also creating a circular economy.

For most of its filaments, colorFabb advises makers to print on a heated plate. But for allPHA, a cool plate is preferable. Non-heated beds mean less electricity is needed – less electricity translates to fewer greenhouse gas emissions.

The soft, flexible nature of allPHA does create a learning curve for makers. But because the material is biodegradable, there’s more room for trial and error and less worry that failed projects will end up in landfills for hundreds of years.

In the Murray makerspace, Walters holds a cardboard spool of allPHA filament up to a plastic spool of XT filament. The difference in the materials is obvious. While the allPHA has a more natural texture, the XT filament is shiny. The two filaments are made up of different polymer types.

Specifically, allPHA is made of polyhydroxyalkanoate polymers. These polymers are created via fermentation by bacteria. Different types of bacteria make different PHA polymers. These different polymers are then put together to create a strong, resilient filament.

In a storage room, BeAM keeps allPHA in stock for future projects. The cost of this filament is about 30% more than non-biodegradable filaments. Recognizing the role allPHA could play in reducing campus waste and greenhouse gas emissions, Sustainable Carolina found that it made sense to help fund the initial stock of allPHA.

Breaking Down allPHA Projects

Outside the BeAM makerspace, there’s a place to pay respects to allPHA printed failures. Joel Hopler, a Hanes Art Center/Murray makerspace technical supervisor, points an experimental space in a small, raised planter created earlier this year to show the team how allPHA objects break down. The speed of decomposition depends on the thickness of material, along with compost factors like heat, moisture, and microbial activity.

In the future, BeAM hopes to purchase a grinder to mechanically break down failed allPHA projects. This would provide a jump start to the decomposition process.

The team stays current on scientific literature describing methods for optimizing biodegradation in the environment. This is safe because the material doesn’t produce microplastics during decomposition.

“Carolina students are passionate about the environment,” said Walters. “By creating a more controlled environment, we can give them access to materials they don’t have to worry about and help them establish better habits.”

Photos and Story by Abigail Brewer